We’ve marched, painted, and screamed truth to power—but on nuclear energy, the art world has mostly gone quiet. That silence isn’t neutral. It’s part of the problem.

Author: The Kernel and Ralph Vazquez-Concepcion

The American Painters Who Looked Away

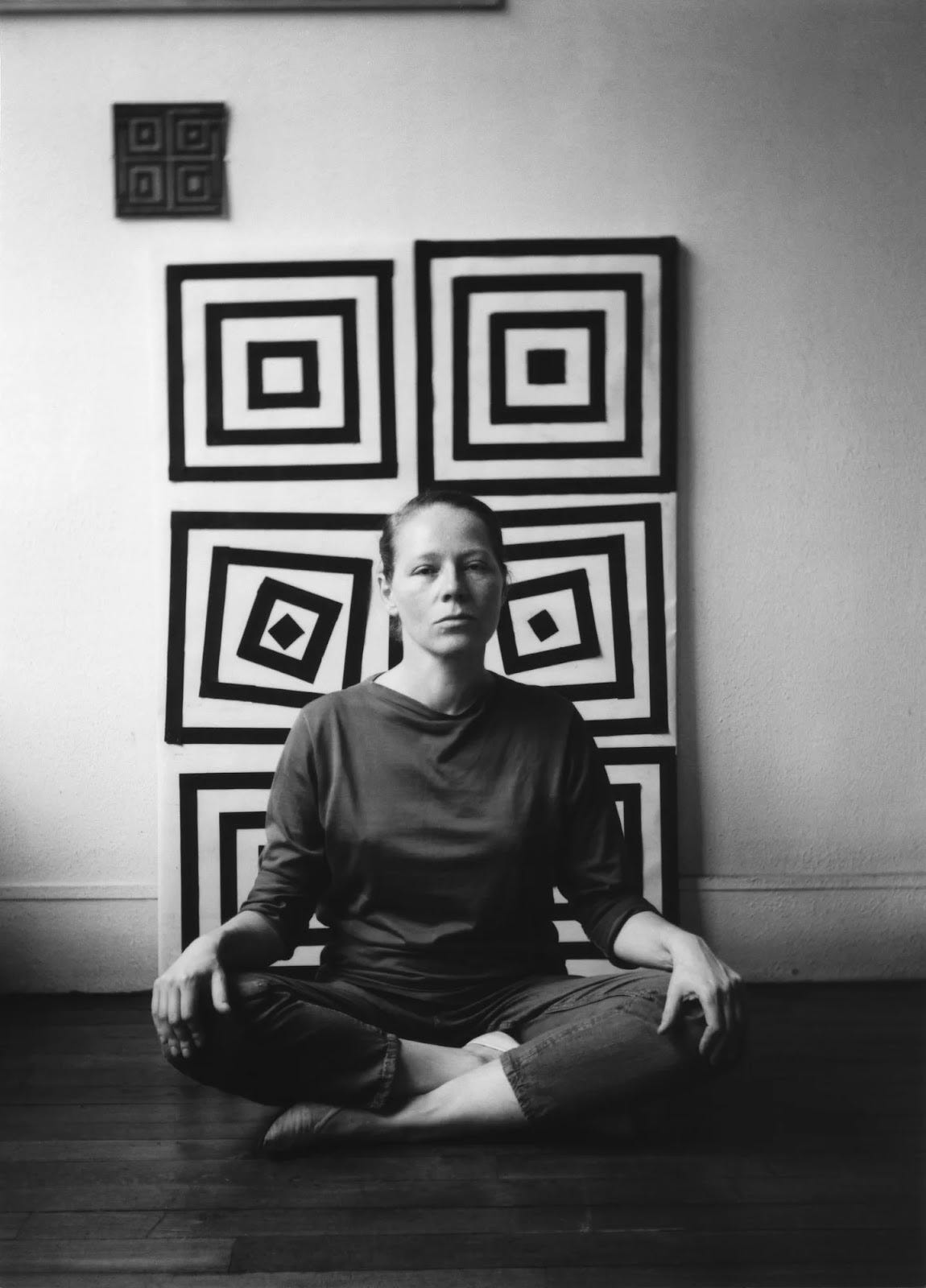

The omission of nuclear energy in the US’s modern and contemporary art canon isn’t limited to conceptual art or design—it runs straight through the American painting canon. My work as a painter seeks to contest this legacy and complement their aesthetic discourse with the progressive gaze they could not convey for whatever reason.

Mid-century American painters rose to global prominence in the postwar years, their canvases treated as cultural exports during the ideological contest of the Cold War. Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still came to symbolize a kind of aesthetic freedom—the “triumph of American painting.” Their work channeled psychological intensity, existential dread, and metaphysical scale. But in their retreat from figuration, from the specificity of politics, they also abandoned the material concerns of the age: infrastructure, industry, and the question that still haunts us—how do we power the future?

Even later movements like Pop Art and Minimalism, despite their engagement with consumer culture and industrial materials, often refused to interrogate the systems that made those materials possible. Andy Warhol gave us electric chairs but no electrification. Donald Judd used anodized aluminum but never addressed where the energy came from to produce it. Ed Ruscha gave us Standard Stations, but the gasoline was just visual rhythm—not critique, not inquiry.

Even when American painters approached the sublime—think Rothko’s cathedrals of color or Still’s jagged monumentalism—it was a spiritual sublime, an internal reckoning—not the nuclear sublime, not the planetary scale of human ingenuity and consequence.

Meanwhile, coal plants dotted the landscape, the interstate highway system stretched across the continent, and nuclear power plants quietly came online, powering millions of homes—and not a single canvas asked, “What does this mean?”

We had artists grappling with mortality, the void, the machine, and even the American myth. But we did not have them grappling with the grid. And in that absence, we lost something.

The question of how we power the future isn’t just technical—it’s cultural. For all its global influence, American painting missed the chance to pose that question at scale.

And Yet, We Know How to Do Better

We’ve done this before. We’ve built visual languages for invisible systems, turned complex technologies into poetry, and shown that art can be a translator, a spotlight, and a scaffolding for the public imagination.

Pioneers of algorithmic and generative art—Vera Molnár, Manfred Mohr, Harold Cohen, and, more recently, Ryoji Ikeda—have demonstrated that aesthetics can bridge data, emotion, precision, and wonder. Molnár’s early plotter drawings, created with punch cards in the 1960s, weren’t just experiments in form—they were declarations that code could be expressive and that machines could participate in visual thought. Mohr pushed abstraction through mathematical logic, mapping algorithmic systems onto canvases that still hum with internal rhythm. Ikeda, whose datamatics series transposes raw numerical data into pulsing sound and blinding light, builds cathedrals of code where viewers don’t just observe—they feel the system.

We’ve already shown that science can be sacred.

The Berlin-based LAS Art Foundation builds on this legacy by commissioning artists to explore the porous boundaries between art, science, and ecological futures. Their exhibitions don’t shy away from technical depth—they embrace it, using it as a material. Artists in their orbit—like Refik Anadol and Libby Heaney—don’t illustrate ideas; they inhabit them, translating quantum logic, machine learning, and climate modeling into immersive environments that stir the senses and provoke inquiry.

Designers and musicians have long understood how to shape public encounters with complexity. Laurie Spiegel’s Music Mouse (1986) gave musicians algorithmic tools to improvise within harmonic constraints, making code and composition inseparable. It wasn’t about showing off technology but making the machine a partner in play. Ryoji Ikeda’s sonic performances function like MRI scans of civilization: cold, precise, overwhelming, and beautiful.

These works prove that artists can engage deeply with science without reducing it to metaphor or aestheticizing it into oblivion. They don’t flatten complexity—they choreograph it. They respect the material. They do the work.

We’ve seen how cultural organizing, even outside high art, has shifted public understanding on a massive scale.

Consider the AIDS crisis. Activists didn’t wait for institutions to catch up. They used posters, zines, wheatpaste murals, performance, and rage. Keith Haring’s radiant babies, the bold typography of Gran Fury’s SILENCE = DEATH, the ACT UP die-ins—these weren’t just reactive gestures. They were part of a cultural infrastructure built to demand science-based public health policy and overturn deadly stigma. They combined visual clarity with moral precision.

Or look at Indigenous artists and collectives today—like Postcommodity, Cannupa Hanska Luger, or the artists in the Water Futures project—who use installation, digital media, sculpture, and storytelling to address sovereignty over land, water, and infrastructure. Their work often braids together ancestral knowledge, environmental science, and legal theory, refusing to separate culture from climate, ritual from resistance.

We know how to build a cultural apparatus around science.

We know how to shift narratives at scale.

We know how to tell stories that make systems feel alive and urgent.

We’ve done it for climate justice, racial justice, public health, and gender equity. We’ve even done it for space travel, the internet, and artificial intelligence.

But we demur when it comes to nuclear energy—still one of the most potent tools to decarbonize the planet. We flinch. We let our old metaphors do the talking. We let the mushroom cloud suck up all the oxygen.

We have the tools.

We have the precedent.

We just haven’t built the framework.

Not yet.

But imagine if we did.

Time to Shift the Frame

The science is not vague or abstract. It is precise, sobering, and unequivocal: We cannot meet our global climate targets without a massive, coordinated deployment of low-carbon energy. And that means all of it—solar, wind, storage, transmission, and yes, nuclear. Not later. Not hypothetically. Now.

According to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, limiting global warming to 1.5°C will require deep, rapid, and sustained reductions in emissions across all sectors—and nuclear power remains one of the few technologies with the reliability, scalability, and density to displace fossil fuels at the speed required (IPCC AR6). Our World in Data shows that nuclear power has the lowest death rate per unit of energy produced—even lower than wind and solar—when accounting for air pollution, accidents, and long-term safety (OWiD, 2023).

And yet, despite this data—despite decades of safe operation, newer designs with passive safety systems, and near-zero emissions—nuclear power remains one of the most misunderstood and maligned forces on the planet.

This is where artists come in.

Not to cheerlead. Not to mythologize. But to do what we do best: ask better questions. Craft sharper metaphors. Refuse easy binaries. We can hold contradiction in our hands like clay. We can shape emotion into inquiry. We can give language and form to things most people haven’t yet dared to feel.

We’ve made war beautiful. We’ve made grief visible. We’ve made silence scream. Indeed, we can make a reactor something more than a threat—something living, something worth debating on its terms.

Nuclear energy is not a utopia. It is not without flaws. But neither is a world where we cling to wind and solar like talismans while quietly burning gas at night. Neither is a world where we pretend land use doesn’t matter, nor are communities repeatedly displaced for lithium, cobalt, or rare earth mining without ethical frameworks.

If we are serious about environmental justice, we must be serious about energy—not just what it looks like but how it works and who it serves.

That means letting go of the narratives we inherited—the ones painted in ash and fear—the ones we never questioned because they made such compelling album art. That means telling new stories—messy, interdisciplinary, vulnerable ones—stories that begin not with catastrophe but with possibility.

Because here’s the truth: the future is already under construction. The blueprints are drafted in policy labs, community councils, engineering firms, and cooling towers. Whether we like it or not, it will be built—with or without our aesthetic approval.

But it will be better—brilliant, human, grounded, and just—if we are part of the conversation.

So this is the invitation:

To the painters. The musicians. The designers. The poets. The educators. The curators. The filmmakers. The dreamers. Bring your fear. Bring your doubt. But also bring your brilliance. Let’s look again. Let’s ask harder. Let’s be brave enough to imagine energy not as punishment or profit but as care. Let’s shift the frame.

Because the planet is already shifting beneath our feet.

And we—if we dare—can help shape what comes next.

Ralph Vázquez-Concepción is a visual artist and high school librarian based in San Francisco. His work explores the emotional impact of environmental trauma and the political aesthetics of energy. He has exhibited internationally and advocates for science literacy in schools and public culture.

More of Ralph’s work can be seen here.

References and Further Reading

IPCC AR6 Report – Mitigation of Climate ChangeIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2022).

Our World in Data – What are the safest and cleanest sources of energy?Roser, M., Ritchie, H., & Ortiz-Ospina, E.

World Health Organization – Air Pollution and HealthWHO Fact Sheet (2021).

IAEA – Nuclear Reimagined: Artists Unveil New Images of Nuclear PowerInternational Atomic Energy Agency (2022).

Lunatum Magazine – Anna Dumitriu: Bioart, Ethics, and the Invisible WorldLunatum, Interview Feature (2022).

Linköping University – Nuclear Natures: Art and Science at the Intersection of Energy and EcologyLinköping University Newsroom (2022).

Oregon ArtsWatch – Michael Brophy’s Latest Paintings Engage with the Hanford Nuclear SiteHall, B. (2022).

Wikipedia – Christine Corday and Her Collaboration with ITER

Bitter Winter – Italy’s Nuclear Art and Enrico BajIntrovigne, M. (2020).

Espionart – African Artists in the Soviet UnionEspionart Blog (2013).

LAS Art Foundation – Art at the Intersection of Science and Technology Berlin-based cultural institution for commissioning future-oriented art.

Lazerian – Tech-Inspired Art Movements: How Technology Shaped ArtLazerian Design Blog (2021).