Artists have mobilized global movements and reshaped public opinion. But when it comes to nuclear power, we’ve mostly chosen to say nothing, and silence is part of the problem.

Artists have shaped revolutions, aestheticized labor, mourned wars, and dreamed utopias into form. We’ve carved monuments out of resistance and laced our dissent with beauty. We have challenged empire, religion, and capital. But we have mostly gone missing on the question of energy—how we power life itself—specifically nuclear energy.

And that absence has come at a cost.

The art world has never been shy about interrogating power. We deconstruct systems, visualize inequality, unearth buried histories, and turn abstraction into action. We elevate what policy documents can’t hold: feeling, contradiction, grief, rage. We give shape to what’s invisible.

But somehow, when it comes to energy—and especially nuclear energy—we flinch. We’ve avoided it and dodged it. Or worse, flattened it into the same Cold War-era anxieties that have calcified into aesthetic tropes.

I know where that fear comes from. I was cracked open by the punk scene in San Juan in the ’00s. We traded bootleg CD’s and screen-printed shirts in alleyways and squats, where every show was a molotov cocktail of sound and ideology. We screamed about imperialism, environmental collapse, corporate greed, and yes—nuclear apocalypse. The fear was inherited. The dread was absolute. We felt we were living on the edge of something irreversible.

But here’s the thing: I carried that fear into adulthood and examined it. I pulled it apart like a guitar amp that buzzes wrong. What I discovered was that the dread we were raised on was incomplete. It was aestheticized, mythologized—but it wasn’t entirely factual.

There is no reason to panic.

There is reason to think, to re-evaluate, to ask better questions.

Now, as a visual artist and a public school librarian, I stand in front of students who will inherit a planet powered by clean, resilient systems or scorched by fossil fuels and indecision. They ask me about nuclear. And when they do, I don’t show them The Day After or hand them a Discharge lyric sheet. I show them data. I show them cooling towers and seismically stabilized reactor sites. I show them maps of low-carbon grids and designs for advanced fission and fusion systems. I show them the possibilities.

Because they deserve better than our silence.

And yet, outside the classroom—in galleries, biennials, and white cubes where culture crystallizes—the conversation is still stuck. Nuance is still missing. Nuclear is treated as a visual metaphor for catastrophe or avoided altogether.

We have the language to discuss race, gender, land, labor, surveillance, and extinction. But we look away when it comes to energy—the material base of everything. We conflate complexity with complicity, and so we stay quiet.

But silence, too, is a position. And in this case, it’s a dangerous one.

The Visual Canon of Anti-Nuclear Fear

It’s not that artists haven’t engaged with nuclear themes—far from it. The detonation of the atomic bomb didn’t just split atoms; it split time, aesthetics, and morality. It seeded an entire epoch of artistic reckoning, and its radioactive plume drifted through every corner of global culture.

The atomic bomb created an aesthetic shockwave that reverberated through the 20th century—and we responded with brilliance, fury, and emotional acuity. But we responded almost exclusively to fear.

Enrico Baj, Two Children in the Nuclear Night (1956)

Enrico Baj’s Two Children in the Nuclear Night (1956) is a twisted collage-based cry against annihilation in Italy. The figures are distorted, gouged by violence, their innocence consumed by abstract dread. Baj, a Dadaist with teeth, wasn’t alone—dozens of Italian artists in the postwar period participated in nucleare art, a loosely affiliated movement grappling with atomic unease. But not one dared to ask: What if this power could serve life instead of ending it?

Iri and Toshi Maruki’s Hiroshima Panels, Fire Panel, 1950

In Japan, where the shadows of Hiroshima and Nagasaki lengthen over every canvas, Iri and Toshi Maruki’s Hiroshima Panels (1950–1982) became one of the most sustained artistic testimonies to nuclear trauma. These sprawling works—fifteen large-scale panels in total—chronicle charred bodies, keloid-scarred children, and landscapes turned to ash. As a child of Puerto Rico’s colonial entanglements, I felt haunted the first time I saw them in a documentary. I felt their moral gravity. They are undeniable. But they are also, again, only one side of the story.

The 1980s No Nukes movement crystallized into a cultural force in the United States. Bruce Springsteen, Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Crosby, Stills & Nash performed to packed stadiums under banners reading “Stop the Madness.” The concerts were urgent, necessary, and iconic. The posters—sunsets bisected by missiles, melting Earths, glowing children—became artifacts of resistance. I remember seeing those prints still hanging in community centers when I visited New York as a teenager in the early 2000s. They’d become part of the progressive visual wallpaper: warm-toned, deeply human, and locked in a framework that equated radiation with evil.

Punk didn’t miss its cue either. Bands like Crass, Subhumans, and Dead Kennedys wrapped their visual and lyrical identities in radioactive dread. “Kill the Poor,” “Nagasaki Nightmare,” and “Bleed for Me” weren’t just songs—they were manifestos of anti-nuclear fury. Nuclear annihilation was the bassline of our discontent. I moshed to it. I lived inside it. But that rage never turned its gaze to the reactor core of truth: energy is power, and how we generate it matters.

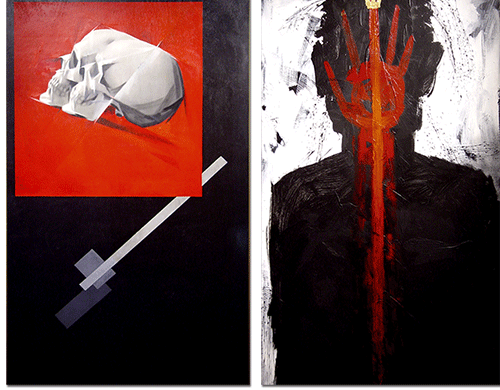

Komar and Melamid, Double Self-Portrait (from Anarchistic Synthesism series), 1985.

Even in the former Soviet Union—where nuclear power was treated as a mark of national strength—the arts had little space for nuance. After Chernobyl in 1986, the cultural response was saturated with despair, censorship, and ghost stories. But even before the meltdown, conceptual artists like Komar and Melamid were already interrogating the disconnect between Soviet utopian promises and authoritarian control. Their ironic series Nostalgic Socialist Realism and The People’s Choice used state iconography to reveal the absurdities beneath. And yet, even they, like so many, never reframed nuclear energy as a civic good worth reclaiming—only as another mechanism of ideological betrayal.

Paintings from Komar & Melamid’s “Nostalgic Socialist Realism” series. Photo by Ben Davis.

The result of all this? A legacy of artistic engagement that has been visually potent, emotionally honest, politically radical—and still, radically incomplete.

Because here’s the truth: most of these works never made space for nuclear energy. They focused on weapons, fallout, and death. Understandably so. But the nuance got flattened. A mushroom cloud became shorthand for everything wrong with the modern world. Nuclear power was framed as an inherent evil, not a tool with duality. Not a system, a technology, or a question of implementation. Just evil.

And we stopped looking closer.

We stopped asking: What if splitting the atom wasn’t the end of the world but the beginning of a different one? One with fewer emissions, fewer fossil-fueled wars, and fewer preventable deaths from air pollution—which, according to the WHO, still kills over 7 million people per year globally (WHO, 2021).

Nuclear energy is the second most scalable source of low-carbon power after hydropower, yet it has received a fraction of the visual support. We, as artists, have rarely rallied behind it.

Go to Our World in Data and compare mortality rates by energy source. You’ll find something stunning: nuclear energy has the lowest death rate per terawatt-hour of any energy source—even lower than solar (Our World in Data). But no mural celebrates that. No installation brings that to life. No biennial has dared to make that emotional.

Instead, we are still haunted by the mushroom cloud—flattening nuance into iconography.

I don’t say this to diminish the trauma. I say it because the trauma has colonized the narrative. We’ve let one image—one symbol—stand in for an entire technological landscape, and we’ve paid the price in stalled policy, cultural confusion, and climate inertia.

Nuclear energy deserves a better shot. And so do we.

The Silence That Followed

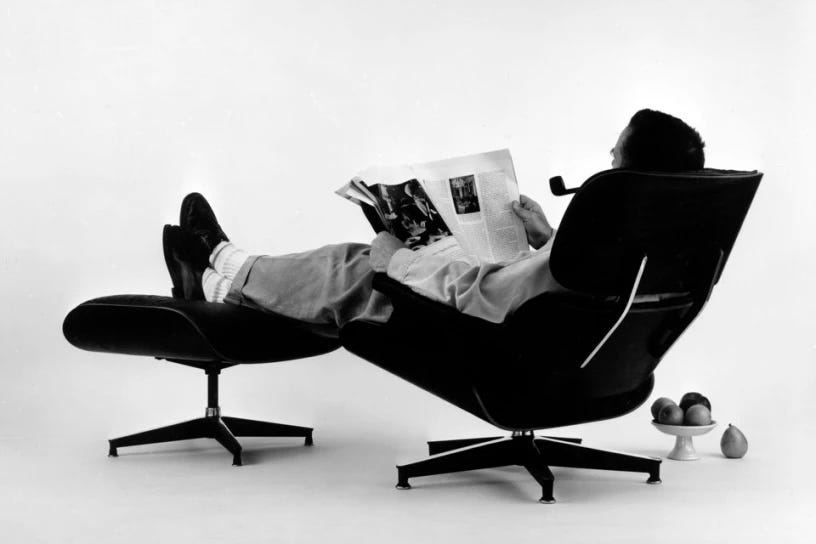

Charles Eames in the plywood lounge chair and ottoman, 1956

While anti-nuclear narratives flourished across visual culture, there has been a striking lack of sustained engagement with the peaceful, civilian applications of nuclear technology. Designers like Raymond Loewy, Charles, and Ray Eames helped craft the aesthetics of the atomic age—streamlining it, rendering it palatable, photographing it into modernity—but they largely dodged the politics of energy itself. Their work danced around power without asking how power should be generated or who it should serve.

Even the ambitious collective Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which brought together artists like Robert Rauschenberg and engineers from Bell Labs in the 1960s, failed to grapple with infrastructure meaningfully. They celebrated systems, interactivity, and human-machine hybridity—but never touched the reactor core, never looked at where the electricity came from. No major museum retrospective has ever directly tackled nuclear energy’s complexity. No blockbuster documentary has asked what a pro-nuclear future might look like emotionally: just silence—or worse, a repetition of tropes.

Meanwhile, anti-nuclear sentiment became cultural wallpaper. It embedded itself in our movies, our punk lyrics, our protest posters—almost always conflating nuclear weapons with nuclear energy. For decades, the narrative stayed simple: nuclear = evil—radiation = apocalypse. And the art world reinforced that equation through its curatorial absences, one-note activism, and refusal to look again.

But the silence is no longer sustainable. A new generation of artists—some emerging from bio art, others from landscape and speculative design—is starting to push back against the binary. They are asking not whether we should fear nuclear but what we are missing when we only see the mushroom cloud.

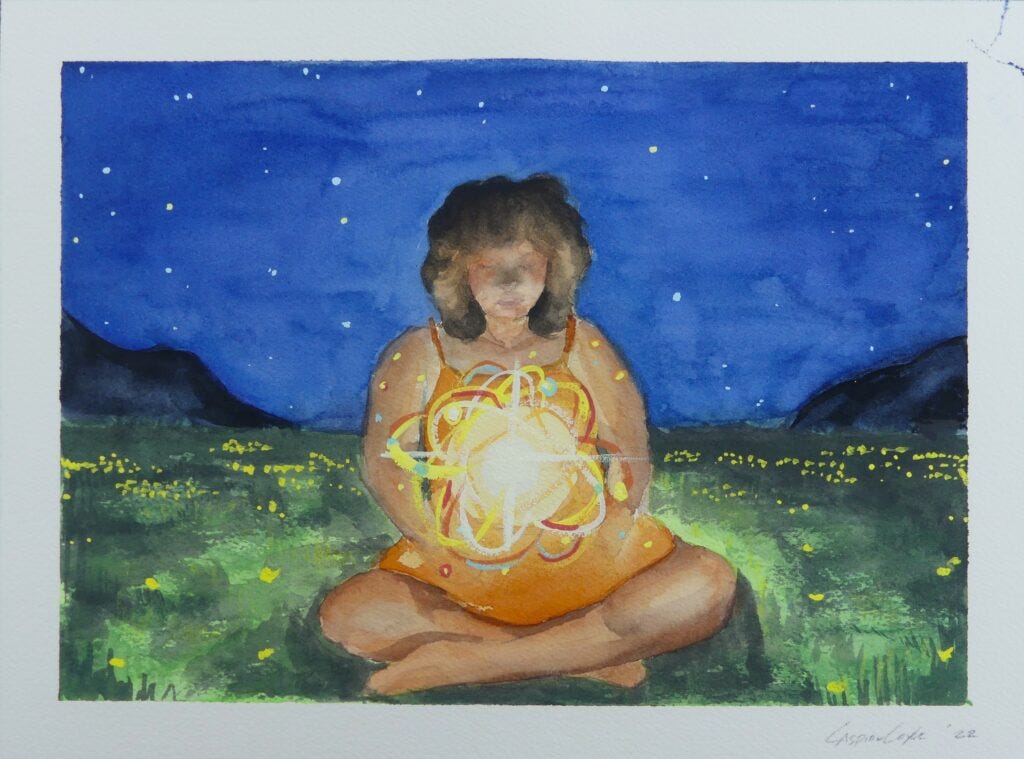

“Manifesting Greatness”, Caspian Coyle, 2022

One example came in 2022 when the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) hosted its first global art competition to reimagine nuclear power. Among the winners was Caspian Coyle, whose painting depicted flowers and a human being growing near a reactor, gently visualizing coexistence rather than catastrophe (IAEA, 2022).

Bioartists are also beginning to venture into nuclear themes with complexity and care. British artist Anna Dumitriu, known for her collaborations with microbiologists and synthetic biologists, creates installations that ask what biotechnology and environmental science can teach us about the future. While her work does not focus solely on nuclear energy, her practice offers a model for how artists can collaborate meaningfully with scientists, producing work that interrogates rather than condemns (Lunatum, 2022).

At Linköping University in Sweden, the Nuclear Natures initiative invites artists to work alongside researchers studying nuclear power’s ecological and infrastructural legacies. Their exhibitions ask how we visualize waste, radiation, and time scales beyond a human lifespan (LiU, 2022).

Michael Brophy in front of his painting Reach: Face at the Harold and Arlene Schnitzer Gallery at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. Photo: Josie Brown

Painter Michael Brophy, in his Reach series, engages with the landscape around the Hanford Nuclear Site in Washington State—the site of plutonium production during WWII and the Cold War. Rather than moralizing, Brophy’s work considers the human and environmental consequences of industrial progress, asking how we reconcile legacy with necessity (Oregon ArtsWatch, 2022).

Christine Corday with the metal ingot that forms the basis of “Sans Titre.” Courtesy Corday Studio 2020.

Meanwhile, conceptual sculptor Christine Corday has collaborated with ITER—the international nuclear fusion megaproject—to develop artistic interventions inside the facility itself. Her large-scale work “Sans Titre” sits not as decoration but as a durational, interpretive presence embedded within the architecture of humanity’s attempt to create a miniature star on Earth (Wikipedia: Christine Corday).

These artists are not producing propaganda. They are producing inquiry. They open imaginative spaces around technologies that have long been locked behind fear or bureaucracy. Their work asks the art world to re-engage—critically, bravely, and with intellectual humility.

Because nuclear is not one thing; it is history, but it is also infrastructure. It is a risk, yes, but it is also resilience. Above all, it is a question of scale: the scale of the problems we face and the scale of the tools we need to solve them.

We must find the courage, as artists, to re-enter the conversation—not to cheerlead but to challenge better. We must see clearly. We must offer what only art can: emotional depth, material complexity, and cultural permission to imagine again.

Ralph Vázquez-Concepción is a visual artist and high school librarian based in San Francisco. His work explores the emotional impact of environmental trauma and the political aesthetics of energy. He has exhibited internationally and advocates for science literacy in schools and public culture.

More of Ralph’s work can be seen at here.

With inspiration to create art that reflects the benefits of nuclear energy, Generation Atomic and the IAEA are hosting the Nuclear Pop Art Competition. Submissions are still being accepted through April 14th 2025.